International Day of Women in Science: interview with Fabienne and Sabrina

February 11 is the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, a day recognised by UNESCO. According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 33.3% of scientists are women. This percentage is of the same order of magnitude as that of female researchers at the Royal Observatory of Belgium, which is between 30 and 35% women among its scientific staff. To mark the occasion, we gave the floor to Fabienne Collin, a seismologist, and Sabrina Bechet, a solar physicist, who share their experiences of their work at the Observatory.

What field do you work in?

Fabienne Collin: I work in seismology, the study of earthquakes that occur in Belgium and abroad.

Sabrina Bechet: I work in solar physics, more specifically on optical solar observations from the Uccle USET station at the Royal Observatory of Belgium. Among other things, sunspot drawings are made there every day.

How important is this field?

F. C.: The knowledge we accumulate through seismology gives us a better understanding of the subsoil and its dynamics. This field is important for characterising regions where earthquakes may occur. This provides important parameters for setting construction standards for works of art (dams, nuclear power stations, SEVEN sites), but also for hospitals, emergency aid centres and so on.

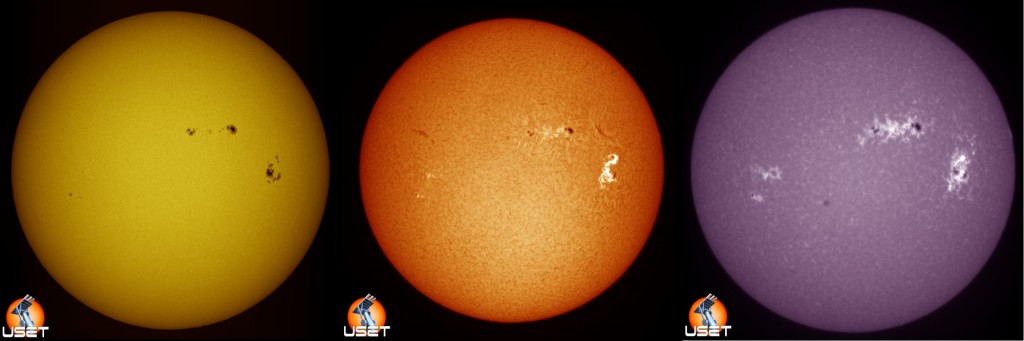

S. B.: Sunspots are regions that are darker than the rest of the Sun’s surface and they represent a direct manifestation of the surface magnetic field. At Uccle, drawings have been made since 1940, making it one of the oldest data collections in the world. Galileo is often credited with being one of the first astronomers to observe and draw sunspots, so there have been drawings of sunspots since the 17th century. Among other things, these observations help us to understand the long-term evolution of the Sun’s magnetic activity. This activity occurs in an 11-year cycle, so it takes several decades to study several cycles, hence the importance of long-term observations. As well as drawings, we take images of the Sun in different wavelengths.

Are there many female researchers in this field?

F. C.: There are still very few women researchers in this field. I’m the only statutory researcher in Belgium.

S. B.: In the field of instrumentation and observations as such, the majority are still men, with a few notable exceptions such as Hisako Koyama, a 20th-century Japanese astronomer who observed sunspots for over forty years. In terms of data processing and scientific analysis, we are fairly close to parity.

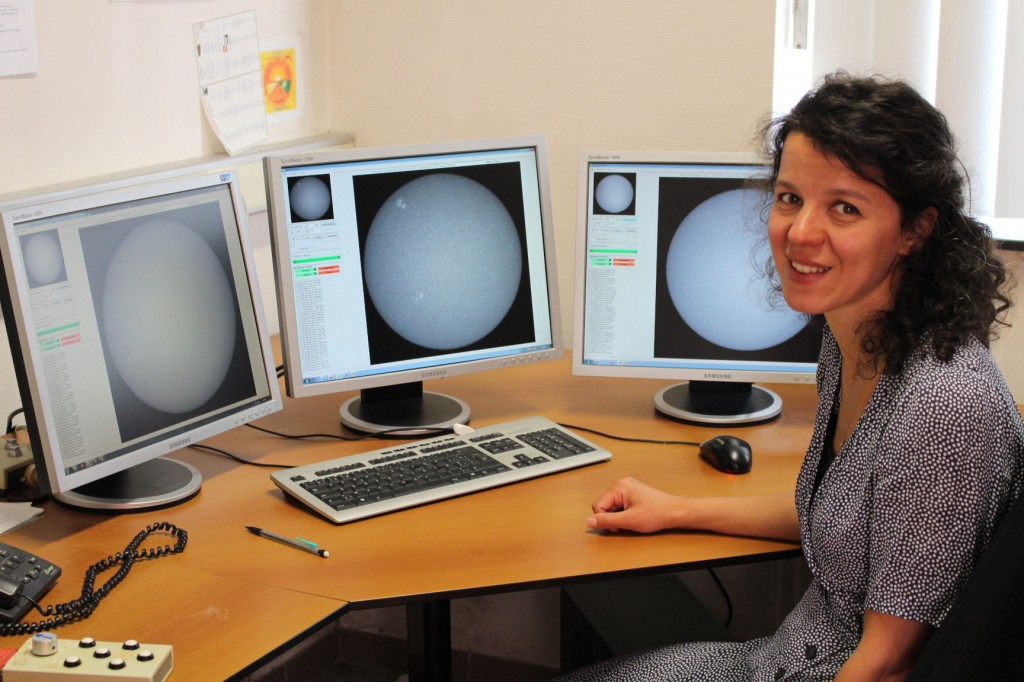

Photo of Sabrina Bechet in the USET control room. The computer screens show the sun in different wavelengths.

What themes and research questions are you working on? What specific activities do you carry out?

F. C.: My work is divided into various operational tasks. Among other things, I’m responsible for the Belgian seismic network, i.e. I look after the maintenance of the seismic stations spread across the whole country. I measure the phases of teleseisms (distant earthquakes) on the signals from our stations and make sure that the resulting bulletins are sent to the ISC (International Seismological Centre) on time. The Observatory has been carrying out this task for over a century. The ISC collects all the phases measured around the world to pinpoint the location of earthquakes as accurately as possible. This enables many researchers around the world to use reliable data for their research, particularly in Earth tomography.

As for my other tasks, I look after the preservation of the seismology archives (old seismograms, old technical documents, etc.) and I’m also available to provide information to the public during earthquakes in Belgium or abroad, by telephone or email. I run workshops (presentation and handling of instruments) during the observation internships or the Open Days at the Observatory.

I also sometimes go into schools to explain our profession to the children. As a team, we also go out into the field to install temporary measuring instruments as part of a local study. Whatever the weather. It’s best to be well equipped and not be afraid of getting your shoes (and clothes) dirty. The tasks in the field are divided up according to each person’s skills, and I’ve sometimes had to work with a spade. For these different activities, it doesn’t really matter whether I’m a man or a woman. What’s important is thoroughness, patience, availability and a sense of human contact.

S. B.: The sunspot data recorded over the long term helps us to better understand the Sun’s magnetic activity and to constrain the advanced models that explain the generation of the magnetic field from one cycle to the next. The images can also be used to study different magnetic structures on the Sun’s surface. In this way, we can compile catalogues to study their properties statistically.

Another research theme in which I am involved is the connection between what we see at the surface of the Sun and the flux measured for other solar-type stars. For the latter, we don’t have surface resolution and we therefore try to explain the flux variations on the basis of the structures visible on the surface of the Sun. In the images (see the figure below), we can also capture transient events such as solar flares, which are localised regions that become intensely bright for a few minutes. They are the site of a release of magnetic energy that can heat the solar atmosphere to several million degrees.

In practice, part of my work involves the instrumentation, its maintenance and modernisation, and the IT development of the data processing chain. Another part involves the scientific exploitation of the data, in particular the development of image processing algorithms to calibrate the images or automatically detect certain structures. So there’s a wide variety of tasks in my job.

Images of the Sun taken on 06/09/2017 in different wavelengths. The two image on the right show two bright ribbons corresponding to a solar flare. Credits: USET/SIDC/ORB-KSB.

What collaborations do you have in this area (within the Observatory or outside)?

F. C.: For the seismic stations in the Belgian networks, I have three collaborators I can rely on to do this. At international level, we are linked to the ISC.

S. B.: At the Observatory, there is a team of several people involved in solar observation, with very varied and complementary backgrounds, ranging from the very technical to the very scientific. At international level, there are around fifteen institutes that make observations with the same kind of instruments and with which we collaborate. It is important to have observatories at different longitudes to avoid interruptions to observations due to the day-night cycle. These observatories are therefore sometimes located at the other end of the world.

What motivates you, what attracts you to this activity?

F. C.: When I had to specialise in my career, the earthquake in Liège had only just happened. In previous years, there had been several destructive earthquakes around the world. I felt it was important to understand these phenomena better so that I could ‘save’ lives. Over the years, I’ve learnt a lot about the physics of the globe, earthquakes and their unpredictable nature. Today, I do my best to pass on this knowledge to others. Through my measurements, I stay motivated in the knowledge that it helps others to make progress.

S. B.: I find that observing the Sun is a constant source of wonder, because of the sheer diversity of phenomena visible on its surface. More generally, solar physics is a very active field, with many open questions and new observations that are gradually leading to answers.

What do you like about your work?

F. C.: In my work, I like the team spirit, the mutual support between colleagues and the exchange of ideas. I always like to learn and pass on what I know to the public.

S. B.: I like the variety of tasks and the fact that we can work on the different aspects of observations, from data acquisition to exploitation. It gives you an overall view of what’s going on.

If you had a magic wand, what would you change about your work?

F. C.: That’s a very good question. I’ve never played with a magic wand. I’d like to have an even better working environment. We’re on the plateau in Uccle, a haven of greenery and calm. The only problem is that our offices are very old. I would like to have a bit more thermal ‘comfort’, accessibility, storage organisation and order. As for the rest, I have very nice colleagues and I organise my work as I see fit, while remaining reactive in emergencies.

S. B.: Like any job, there are some aspects that aren’t so much fun, but which are necessary. For me, it would mean having fewer administrative tasks.